Blockchains. Tokens. Web3. On-chain, off-chain, rare, SuperRare. The amount of jargon that accompanies crypto art, or NFT art, is enough to make even the most educated reader’s eyes glaze over. The problem is, in order to look at crypto art, in order to engage with it either as an artist, viewer, or collector, you have to speak the language.

There is no doubt that crypto art has the potential to transform visual art as we know it. In fact, it’s already doing so. But this has less to do with what the art looks like, and more to do with how we can look at it. And the truth of the matter is, unless you are an avid lurker on SuperRare, Rarible, or OpenSea — just some of the major NFT art marketplaces — you will probably never see most of it.

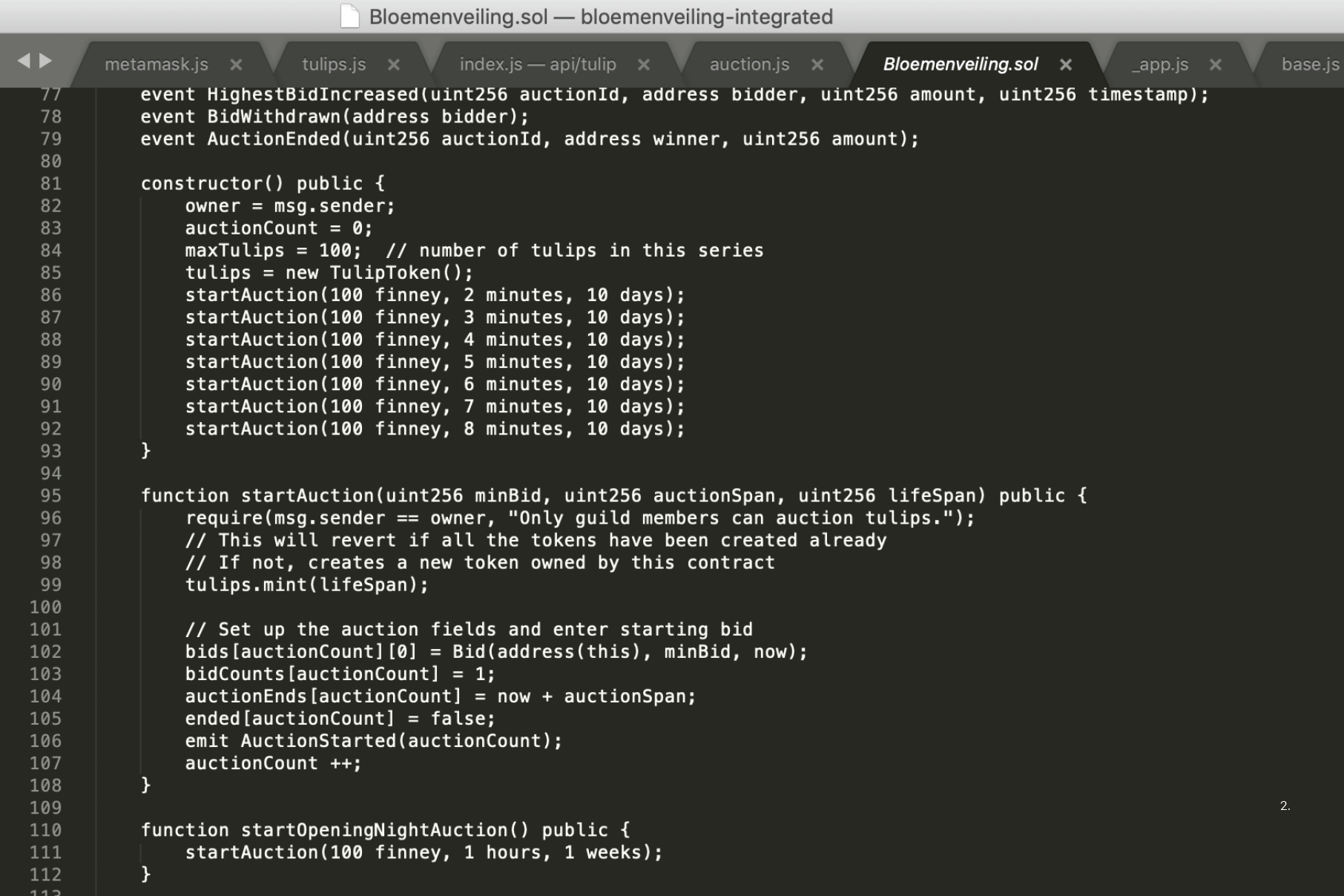

Artist Anna Ridler aptly captures the black-box effect of the NFT phenomenon: “The blockchain,” she writes, “is an abstract concept and does not lend itself immediately to visual or experiential expression. It is a series of complex, interconnected systems that are usually hidden from the end user.” ¹ But it’s not just the process that’s hidden; to an extent, so are the artworks. Crypto art marketplaces thrive behind a paywall that, to the uninitiated, are as shrouded in mystery as a multi-level marketing scheme.

SuperRare, for example, lets me scroll through its marketplace, but if I want to interact, even merely to “favorite” an artwork, I need to create an account. But this isn’t as easy as entering my name and email. It asks me for information on my “wallet,” my crypto wallet, which I don’t have. I try to understand what a wallet is, only to be met with more impenetrable jargon. So I give up. To participate in the world of crypto art, you don’t just have to invest your money in a new, risky art form. This is not simply a new kind of art market. It’s a new creator economy. Like the entrepreneur Moxie Marlinspike, those who remain skeptical about crypto art call themselves non-believers, suggesting that there is a whole belief system at play. This was never the case with new media art of the past.

As a historian of art and technology who specializes in the early days of digital art — the 1960s and 70s — I am often asked what I think about NFTs, and truthfully, I avoided understanding them for some time. This came not from a place of dismissal or snobbery, but genuine perplexity at this phenomenon that seemed to crop up overnight like an invasive mushroom. In late 2020 I taught an undergraduate survey course called “New Media Art since the 19th century,” which ended on a module about web-based and post-digital art. We discussed Petra Cortright, Martine Syms, Trevor Paglen, Hito Steyerl. NFT art wasn’t even on my radar, nor that of my Gen Z students. It’s incredible how quickly this technology, and therefore this community and its discourse, have grown.

Like the technology it describes, the language of crypto art moves fast, and it’s hard to keep up. Rather than attempting to define this peculiar vocabulary (your multiple open tabs will do that for you), I’d like to consider what happens when we describe a new art form with a language more complicated than the technology behind it.

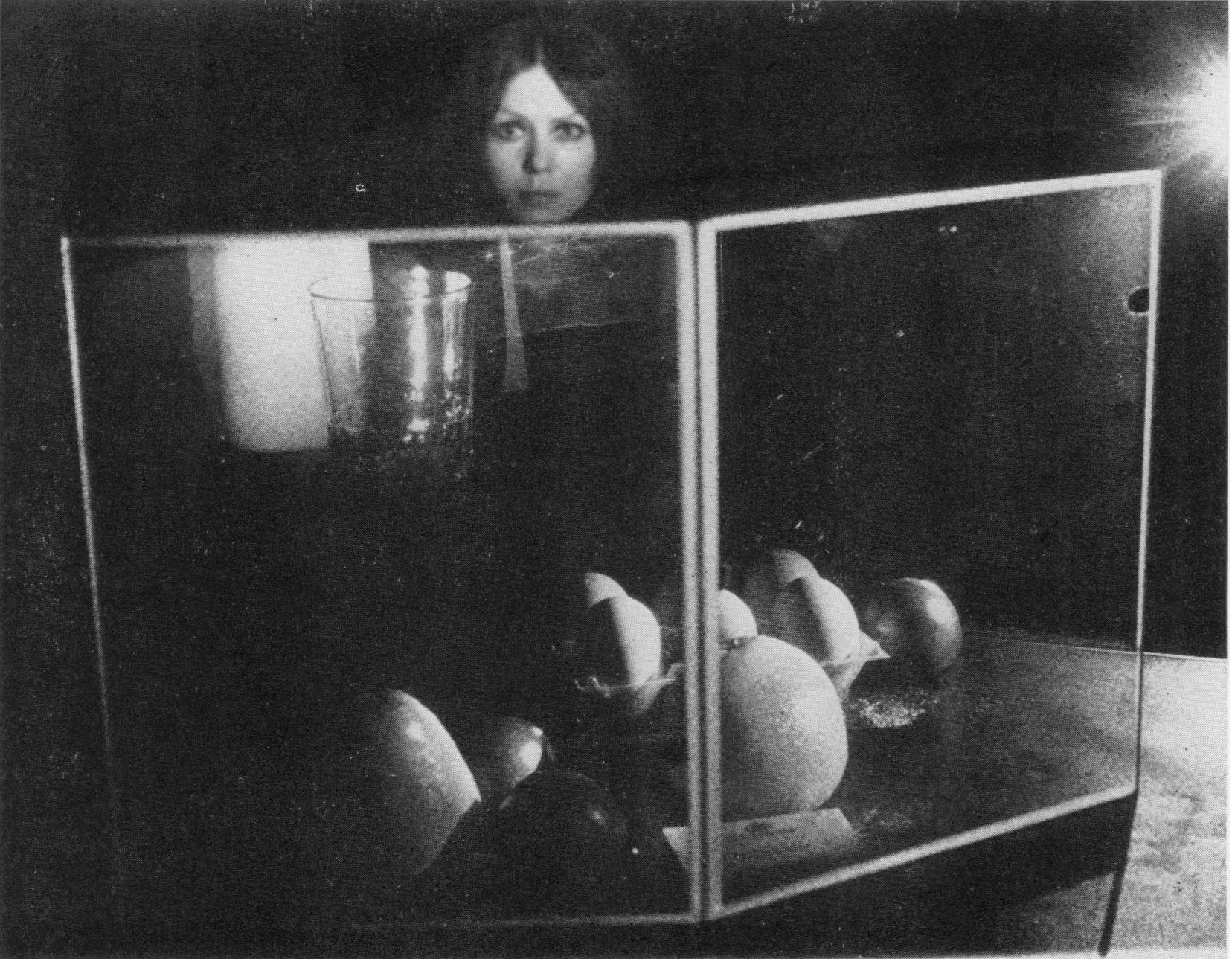

This is not the first time in history that art made with emerging technology has baffled, bemused, and enraged the art world and the media alike. First, there was photography, which took nearly a century to be accepted as a legitimate art form — that is to say, worth spending art museum budgets on collecting and exhibiting. In the late 1960s, artists began experimenting with a new imaging technology called holography, which used lasers to produce three-dimensional images called holograms. “It’s not yet perfect, but [the] holograph is [the] photo of [the] future,” declared a critic for the Chicago Tribune on November 25, 1981. Others dismissed it as a gimmick, calling the deluge of iridescent products “holokitsch.” This did not deter its practitioners from keeping on in their basement laboratories, and its champions from opening museums of holography in most major cities. Interest waned in the late 1990s, however, and holography museums and university programs rapidly folded. While there is still a sizeable international community of holographers active today (the public Facebook group, Holography, of which I am a member, has 2,400 members), there is virtually no market for the objects they make, and many of its veterans will speak bitterly about how they were unfairly sidelined from the mainstream art world. If Margaret Benyon (1940-2016), the first artist-holographer, were alive today, she would tell them: “I told you so.”

Benyon learned holography in Nottingham in 1968, the same year the more famous artist Bruce Nauman worked with Conductron Corporation in Ann Arbor to make a series of holograms. Benyon maintained a writing practice alongside her prolific holography career, publishing nearly thirty articles over the next two decades. Having been a painter before turning to holography, she wrote fluently about the mainstream art world and holography’s marginal relationship to it. Over the years, her tone moved from frustration to disappointment, as she lamented critics’ unwillingness to understanding holography, and holographers’ unwillingness to talk to anyone outside their “embryo art world within the holography world.” ² In 1992 she wrote, exasperated, “We need to get out of this ghetto.” ³

In his sociological study of art worlds, Howard Becker underscores their collective nature: “If practicing artists want their work accepted as art, they will have to persuade the appropriate people to certify it as art.” ⁴ But how? Becker would have advised the holographers to learn art critics’ language, especially if the critics weren’t willing to learn theirs. Benyon agreed, writing that “a critical language, a vocabulary, needs to be developed before holography can find its own voice.” ⁵ This isn’t exactly a two-way street: Art critics and historians hold more power in their words than do most artists. But that doesn’t mean their language is any easier to understand. The word “artspeak” has been around since at least 1975, and everyone in the art world remembers the article, “International Art English,” published in Triple Canopy, that went viral a decade ago now. ⁶

In this text, Alix Rule and David Levine gave a hilarious, compelling description of the linguistic peculiarity of IAE — those cringeworthy turns of phrase that sound like a Rosalind Krauss bot — and discussed its symbolic significance to the art world — its “precious” power to “deem things and ideas significant and critical.” Taking this article very seriously, I wrote my master’s thesis in applied linguistics shortly after this article came out, using corpus linguistic methods to show how IAE’s authoritative voice is related to its linguistic similarity to academic English, and how the journal October’s dissemination of French critical theory had a major linguistic impact on the less scholarly but equally prestigious publication Artforum, from the mid-1970s onward. In sum, it’s not what IAE says that deems the art important; it’s how IAE says it.

The I in IAE remains to be investigated, but the dominance of English in international artspeak recalls another domain in which English has long prevailed: Computing, specifically programming languages. Since the US and UK pioneered the electronic computing industry in the 1940s, most programming languages have used English commands, meaning programmers need to know some English to “talk” to their computers. This is especially evident in the writing of artists working with computers in the 1960s and 70s. Whether they were writing in Spanish, French, German, or Japanese, one can always find the English word “random.” These artists, too, belonged to a subculture — “an embryo art world” as Benyon called it — that was not welcomed by the mainstream art world. The problem seems to be that people weren’t, and still aren’t, talking to each other. Each subculture uses its own jargon to gatekeep, and thereby risks falling into an echo chamber.

Margaret Benyon was one of few artists working with post-war technology who was vocal about and critical of its relationship to the military-industrial complex. Writing in the radical feminist journal Heresies in 1981, she called on her peers to counteract actively the connotations of destruction and violence by emphasizing holography’s subversive possibilities. She declared holographic art a “countermeasure” to the laser’s “sinister” applications. ⁷ For Benyon, using lasers to make art — not war — was a political act.

Her own holograms often took an explicitly anti-war stance: An iridescent double exposure of a soldier’s helmet and a bouquet of daisies, a nuclear fission model titled Unclear World (unclear being an anagram of nuclear). Her writing, however, sends a different kind of warning: That counterculture is a double-edged sword. While subcultures can create vibrant communities, when it comes to the art world they inevitably lead to art historical obscurity.

Where Benyon saw the radical potential of holography as a medium to enact change from within systems of power and oppression, she did not have access to analogous systems of power in the art world. Thus her writing, as well as her art, remains marginal. By 2022, we have supposedly moved beyond this center-and-periphery model. The monolithic art world in the latter half of the twentieth century has become more decentralized. Of course, crypto art enthusiasts will tell you, it’s still not decentralized enough. Writer and theorist Penny Rafferty has rightly suggested that using NFT technologies may allow us to “tackle the current economic models within the art world, which are extremely outdated,” for “the rise of the professional artist has not been met with professional infrastructure.” ⁸ But, as Marlinspike wrote in a viral blog post early this year, while decentralization and distributed systems may sound promising, in practice they have only made Web3 “more complicated and more difficult, not less complicated and less difficult” from a structural point of view.

My goal is not to critique the project of decentralization — that is not my area of expertise — but instead to look to art history to address the dangers of obscuring art with the language we use to describe it. Crypto lingo not only alienates potential viewers and critics, it also alienates potential makers. Andrew Ngurumi notes that “artists in the Global South are not as conversant with crypto market spaces and blockchain technology because the knowledge producers inadequately educate and empower them.” ⁹ To be “conversant” implies that one can engage in conversation. But as it stands, only a privileged few are equipped with these linguistic skills, and so people aren’t talking to one another. For an art form that aims to decentralize, it does very little to democratize.

Ethereum, the technology behind the cryptocurrency ETH, waves us in with a gesture of accessibility: “Banking for everyone”! “Not everyone has access to financial services. But all you need to access Ethereum and its lending, borrowing and savings products is an internet connection.” Of course, in a democracy of the 1%, the value of crypto art hinges on its very inaccessibility. Jon Victor points out that even “transfer art,” a form of crypto art designed to change with each new owner, is in practice just passed back and forth between the same person with two different usernames. Am I just talking to myself?

Zsofi Valyi-Nagy is a fellow at the Center for Advanced Studies in the Visual Arts and a PhD candidate in art history at the University of Chicago, where she is writing her dissertation on Hungarian-French computer art pioneer Vera Molnar. Her article on the Australian holographer Paula Dawson will appear in the spring 2022 issue of Art Journal. Zsofi is also a practicing artist and holographer, and is currently based in Berlin on a DAAD fellowship.

___

¹ A Estorick et al. (eds.), “Crypto Art’s Sustainable Trajectory: A Roundtable with Kevin Abosch, Robert Alice, Chloe Diamond, Joe Kennedy, Andrew Ngurumi, Penny Rafferty, and Anna Ridler”, Flash Art, vol. 54, No. 337, Winter 2021, 116.

² M Benyon, “Do We Need an Aesthetics of Holography?”, Leonardo, vol. 25, No. 5, 1992, 414.

³ Benyon, 415.

⁴ HS Becker, Art Worlds, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982, 156.

⁵ Benyon, “Do We Need an Aesthetics of Holography?”, 415.

⁶ The Oxford English Dictionary locates the first appearance of “artspeak” in John F. Moffitt’s book review of Gustaf Cavallius’s “Velázquez’ Las Hilas Deras: An Explication of a Picture Regarding Structure and Associations”, in Art Journal 34, No. 4, 1975, 380. “art, n.1”, OED Online, Oxford: Oxford University Press, December 2021.

⁷ L Blumenthal et al. (eds.), M Benyon, “Unclear World I”, Heresies 4:1, No. 13 – Earthkeeping / Earthshaking: Feminism & Ecology, 1981, 35.

⁸ Estorick et al., “Crypto Art’s Sustainable Trajectory”, 115.

⁹ Estorick et al., 115.