Alex Estorick: The world of generative art is clearly a different place by comparison with the boom of 2021. Yet many recent projects, including those released as part of Cure³, feel more experimental and critical.

Marcelo Soria-Rodríguez: For me, it is a moment for reflection and also a moment of convergence between different areas I’ve been exploring for the past four years. When one steps back, one sees the arcs of one’s activities as well as their real meaning. I spent 13 years of my professional life working in strategy and innovation for BBVA, which is Spain’s second largest bank, focused on understanding what new technologies and open data policy would mean not only for financial services but for people.

Because they have a lot of information about payments and monetary flows in particular locations, banks are able to forecast how different technologies can generate smarter cities. We even launched our own data-based product for retailers to better understand their own geographical areas, which was interesting for small and mid-sized businesses that have tended to lack the same access to data tools as large corporations. Back in 2019, when I was responsible for data strategy at the bank, we developed a proposal to use art and culture as a tool for corporate strategy.

Art has an unrivaled capacity to explore unknown unknowns because it requires one to think outside the box and doesn’t depend only on executable outcomes, unlike corporations.

At the time, the bank was really focused on short-term execution, so Iskra and I ended up quitting the bank simultaneously on the same day. We set out to create our own agency rooted in the idea of art for strategy, but then COVID came along so we decided to focus on the art part.

AE: Speaking of unknown unknowns, isn’t that precisely what generative art is about: exploring emergent possibilities?

MSR: Absolutely. I once wrote an article about the idea of expanding the total cognitive space — also referred to as latent space — a term which often appears in discussions of AI but which refers to the full definition of a system with all its constraints and possibilities. Of course, it is an ideal because one can never fully grasp all the possible forms and shapes that a system might take. When I was working at the bank I often seemed to be able to extract something from somewhere in a way that others might miss, which relied on a weird capacity to synthesize if not an experience of synesthesia.

AE: Your early project for Art Blocks Entretiempos (2022) made such an explicit reference to the works of Sonia and Robert Delauney that it felt like you were playing with a ready-made modernist idiom in order to express a synesthetic sensibility. Is that how you see it?

MSR: Probably, yes. My first attempt at that was actually an earlier project on fx(hash) Contrapuntos (2021), which was a literal synesthetic translation from the musical technique known as counterpoint that was practised by JS Bach. Before I started doing generative art or code art, I was reflecting on the idea of spatial or visual counterpoint, so I used shapes and colors that owed something to the aesthetics of the first half of the 20th century. Entretiempos continued that exploration of the visual language of Orphism in order to expand the idea of a total cognitive space.

However, while producing the artwork, I started to think about timescales, including the time it takes for a work to render as well as the intermediate steps along the way. It seemed to parallel natural processes such as erosion which we often experience only as a slice.

Other processes are too fast for us to see, which is also something I wanted to explore in that artwork as well as in my writings, which are fully intermixed in my practice.

AE: I remember speaking with you in the early days of the magazine about the need to fill a critical vacuum but also to let artists themselves shape the terms by which their own work was evaluated. You were the first artist to write an essay about their practice for RCS, which reflects something of the grassroots, even DIY, spirit of the time. 2021 is often remembered as the year of the NFT boom but it was also the moment generative art went mainstream. What do you remember of your interactions with other artists and collectors at that time because it felt to me like a hype-based economy that wasn’t governed by critical language?

MSR: I got in touch with Art Blocks in January 2021 following an Instagram post by Dmitri Cherniak in which he talked about his upcoming Ringers drop. Back then I was reading all I could about NFTs, learning about token standards and now-extinct platforms such as Async Art. Amid all the chaos, Art Blocks felt like a natural fit with my own practice. It was remarkable to me that a small group of people could really build a release platform, and determine what was of value to them on their own.

Life as we know it can only emerge from chaos, from a permissionless environment and an unregulated mixture of ingredients and energy. Of course, once life has emerged it needs to start regulating itself. Life that remains in dirt and chaos will most probably disappear.

All the hype that came after the initial emergence of Art Blocks was damaging to those life forms that emerged subsequently and even to those forms that had appeared at the beginning.

I believe that a combination of permissionless publishing and education helps people to better manage waves of hype and to support their appreciation of art’s meanings. There needs to be a level of curation in order to help people navigate what is available, but we also need to stop trying to capture value. The problem of crypto art is that while it allows creators to capture the value of their work, the value of art lies primarily in subjective experience and emotions, and you can’t capture that.

In my view, spending too much energy classifying emergent phenomena halts their development, but a complete lack of sense-making probably derives from people clinging to the most basic human behaviors, in this case, greed and hype, which probably damaged the perception of generative art.

Certain collectors who seemed to appreciate the art on Art Blocks in the first instance later sold their entire collections when it became clear that the prices would not continue. It has been disappointing to see certain dynamics play out in the last three years and also worrying to witness the hype cycle reappear in other forms of art.

AE: Do you feel you’ve benefited from dovetailing your art practice with self-reflexive writings?

MSR: I don’t know if it’s necessary or even always an advantage to speak your mind about your own work. However, if you don’t then you are certainly at the mercy of pre-existing tools of contemporary art criticism, postmodern or otherwise.

To me, the digital art scene is blooming at a speed that is impossible to classify. We need to remain open rather than trying to tag things the moment a new tag becomes available. When Tyler Hobbs coined the term “long-form generative art,” all of a sudden everything had to be “long-form.” People didn’t understand that you could choose not to do a long-form project and still be doing generative art, or produce projects that are long-form-ish, or mix hand-coded gen art with AI models that you’ve trained yourself. Certain members of the public get lost at that point and say to you, “this is not canonical” and therefore it’s no good.

My practice is probably a bit hard to understand when viewed from the outside and I’m not sure if my writings are helpful because few people will likely read them anyway. But, for me, my artworks are not discrete objects but part of a mental process that also involves words and music.

AE: Right now you’re testing a new project that uses smart contracts. What can you tell us about that?

MSR: I have certain ideas about making artworks programmable, allowing them to work as ensembles and to become marketplaces in themselves. Smart contracts allow one to explore cognitive science scenarios and I’m interested in baking in such dynamics into my artworks.

AE: Were you interested in Kim Asendorf’s recent project PXL DEX (2025)?

MSR: Yes, that project is really interesting. Such mechanisms involving tokenomics can create a story that people feel attracted to. I’m not going to question whether it is art or not because we all respond to different things. Art can be a pure expression of beauty but it can also expand one’s horizons when used as a research tool for strategy.

Smart contracts are not only about clicking and buying; they force you to do something, creating a friction that brings you closer to the work.

Everything these days has a digital shadow that you can tokenize, for example through NFTs, and therefore a smart contract can act on anything. This is still little explored, but it is something that numerous industries are looking to build upon.

AE: If Web2 involved the reduction of life to a series of datapoints, does Web3 unlock those data as possibilities for activity or performance?

MSR: I believe that dismissing Web3 and blockchains, which have been tainted by scams and scandals in recent years, misses their potential as bearers of freedom. Of course, the adoption of a new technology involves cycles of rejection and maturation, indeed the deeper the capacity of a technology to change established power structures, the slower the change is likely to be. The potential is there for a different Web3 and art has a very specific role in exploring that because it lacks a specific intention.

.png)

AE: It seems to me that over the last couple of years people have made a conscious effort to uncouple what they see as the art object from the NFT, which is to say the token substrate or means of inscription on the blockchain. What I find interesting about the direction in which you’re moving — and you’re not alone here — is that you’ve fully absorbed the aesthetic act, object, or performance into a hybrid, commodified practice of digital artmaking. One potential consequence is that the notion of art as a separate realm of aesthetic experience is replaced by the idea of an experimental, indeed generative, system for social utility.

MSR: Everything is a mashup today and if you look at society, it is as mixed as ever. Life only comes from mixing things and technology can drive that mixing process. When digital art meets a medium that allows it to keep on living as a digital thing then it can acquire new capabilities, including cognitive capabilities. This is a very rich environment to explore and for things to evolve; it is unstoppable.

Complexity generates many things and this is exemplified by nature. Through smart contracts and other technologies digital art becomes a living entity.

Something that I have explored in recent years is interactivity — today’s paintings are able to interact with their surroundings. The first example was my work with Andreas Rau Toccata (2022) that you could actually perform to your liking by changing camera views and other elements. While Centrifugal (2023) reacts to ambient sounds when you turn on the microphone.

My most recent work with Art Blocks Variaciones del Yo (2024) was commissioned by one of the largest collectors of Entretiempos. It has an entire performance system built into it so that not only can it perform on its own but collectors can also do their own thing. Expanding this interactivity and performative capability into the smart contract breathes even more life into a piece such that you don’t even need to own it to enjoy it. That is one of the beautiful things about digital art on the blockchain — ownership can be a much more generous experience than with traditional art because it can invite active rather than passive experiences.

Web2’s frictionless, streaming economy actually steals part of people’s personalities from them because when you’re not required to make any cognitive effort to obtain a service or content then your enjoyment of it is reduced because it has also been reduced to a throwaway form. But there is another way of thinking about collecting as an act of making meaning. Even if a piece is free, collecting it is a way of taking a stance in the world and saying, “this is important to me as an independent human being.”

Life is hard and life makes choices for you if you don’t make them yourself. Being able to express yourself through the act of collecting is important and to collect a work as part of Cure³ is a statement that you can take action through your collecting.

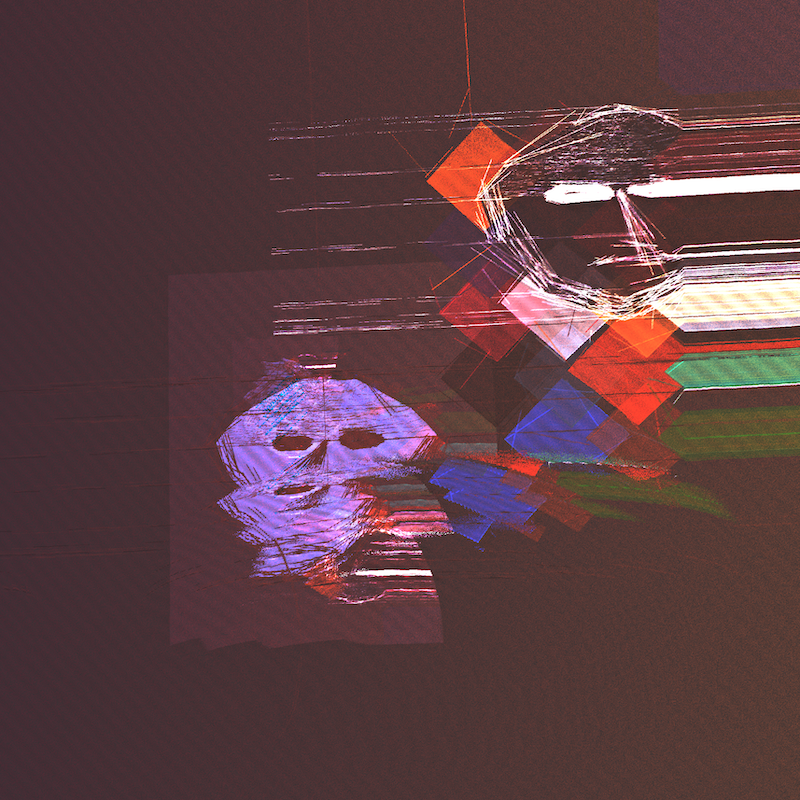

AE: Your recent work for Cure³ is part of a series titled “(are we [all) we are]” that is concerned with cognitive space. But in considering the indeterminacy of cognition you are also grappling with the experience of cognitive decline. How do you view this important body of work?

MSR: My circumstances in life have been quite normal, even comfortable up to now. That said, illness has impacted my family and I’ve always felt a need to do something about it even though I’m not a doctor. My grandfather lived with Parkinson’s before he died and recently my uncle died from complications resulting from Alzheimer’s disease, while another uncle sadly has it too. Having dedicated myself fully to making art, I am determined to use my artistic voice to take action. Just as collecting something is a statement, so creating something is also an action.

These three works all revolve around the idea that illness can cripple your relationship to the world and also change the picture that others have of you because they can see the effects. Nevertheless, there is a core, especially an emotional core that is derived from everything that happens to you in your life along with the material you were built with that configures how you react to things. I wanted to make the point that no matter what illness you have, you are still entitled to a full human existence. No matter how degraded your cognition is, you’re still a person who deserves respect.

The experience of a degenerative disease is obviously different when it touches your loved ones from when you are outside of the situation, but both involve a struggle to relate.

AE: Creative coders of your generation are often concerned with expressing external realities and natural morphologies through code. But the act of using code to explore the inner life of the mind feels rather different. One visual current throughout this series is the way space coheres and disassembles, with the most recent project perhaps the most indeterminate, filled with vestigial figures arranged in rows or else within unsettled compositions. Of course, code is the province of both humans and machines and so it feels as though you are also capturing a wider uncertainty about the human condition.

MSR: We all operate on a spectrum of possibilities with conventions dictating what is normal and then, beyond a certain threshold, what is disease. But what is your perception when you are on the disease side of things? Understanding diverse realities requires empathizing with another mind. The same will be true of artificial minds. It’s unusual to shift your point of experience but, as an artist, if I can engineer a different field of perception, maybe that can invite greater understanding of difference itself.

Right now, AIs without bodies are helping humans a lot and, in time, they may develop a conscience of their own as well as their own notion of what they are. Perhaps AIs will relate not to the output of a generative algorithm but rather to the algorithm itself, which is actually the purest form of the artwork.

Code is closer to the general idea of what an artwork is than any number of possible visual outputs. Machines can likely understand that better than us because they’re native to that space.

To me the algorithm is the idea and then the code is how you implement that idea and then the output of the code is something visual that humans can process with our senses because we cannot process code itself. Very few people can actually say, “this code is beautiful.” In the same way, few people would likely recognize the beauty of a thought or idea prior to it being materialized in an artwork. This was the basis for my project, rêves de papier et l’identité des mèmes (2022-23), which explored the notion of paper as an artwork in itself that materializes an idea originating in code. Instead of transferring an image to paper, I leafcasted colored paper fibers into an image directly according to an algorithm.

Do ideas, or identities for that matter, pre-exist or do we simply latch on to existing identities, as artificial entities might? If all possible combinations of images already exist in latent space then we are not going to generate anything new. Only if we expand language can there be new combinations. That applies to everything: individuals, markets, life.

Marcelo Soria-Rodríguez is an artist and strategist based in Madrid, Spain. Interested in the relationships that span any combination of humans and machines, the role of emotions and questioning established societal and cultural notions in the light of potential new intelligent species entering into our environment. He has exhibited globally, including at Art Singapore, Art Basel Hong Kong, Unit London and Kate Vass Galerie, participating in Bright Moments México City and Finale collections, Art Blocks Curated Series 6, publishing Contrapuntos, one of the highest acclaimed works on Tezos and fx(hash). He also co-founded Databeers, a movement for data literacy present in over 30 cities in ten countries. He has a background in engineering, innovation, strategy and fostering education.

Alex Estorick is Editor-in-Chief at Right Click Save.